“Security” and Capitalism in Singapore was TJC’s first public webinar in 2024. Through the lens of critical criminology, Joe Greener and Eve Yeo examined how “security”, as imposed by Singapore’s authoritarian and capitalist regime, is both mystifying and pacifying in order to stabilise unequal economic and social relations. It is used to justify hierarchical social order and place marginalised groups under intense control.

Read our recap of the webinar below:

Crime as a mystification

Crime and criminalisation are social control strategies deployed by the state to uphold hierarchical social order and the profound inequalities it depends on.

What is or isn’t determined to be “criminal” is primarily shaped by political and economic elites who falsely imagine that a set of morally bankrupt people at the bottom of the social hierarchy are responsible for society’s ills. This illusion obscures the vast amount of avoidable harm, injury and deprivation imposed on the ordinary population by the state and elites, while allowing impunity for others.

For instance, the harm and violence of poverty, labour exploitation, wage theft and environmental degradation as caused by corporations are not considered or constructed as crime, even though the actual damage is far greater than anything that can be caused by people with less power and resources. This means that marginalised peoples are disproportionately subjected to the violences of policing and incarceration.

“Security” to enforce productive labour

Capitalism seeks to stabilise social relations that rest on profound inequality, e.g. exploitation of working people. Mechanisms of ‘security’—such as police, military, surveillance, imprisonment, immigration control, security guards in buildings—make capitalist societies possible by threatening or using violent control against those who are not “playing the game,” complying or participating in capitalist society.

This suppression, through law and institutional power, of non-capitalist forms of subsistence serves to uphold unequal property relations. ‘Security’ can thus be framed as pacification, where it is deployed to make the economy productive and accumulate the wealth and power of the elite and the state.

Let’s examine three modes through which security forcibly creates productive labour, and contextualise these concepts in Singapore:

Dispossession — pacification by control of space

Forcible removal of people from communal modes of survival, underpinning a dependency on waged work and the creation of the working class. Examples include:

- Removing welfare support

- Removing indigenous people from their land

Exploitation — pacification by control of time

Deployment of security to ensure that workers comply with the exploitative terms of their employment, and in a broader sense, comply with working in a capitalist society. Examples include:

- CCTV cameras at the workplace

- Policing drug use

- Policing homelessness

Commodification

Security’s role in ensuring that profit-making is happening across production sectors means security itself becomes an ever-expanding commodity.

Dispossession of Land in Singapore

Land reclamation naturalises dispossession

Land reclamation is one of the Singapore state’s geopolitical strategies to establish sovereignty on so-called new territory ‘reclaimed’ from the sea. Not only does this presuppose that the sea does not have inherent value, but the narrative obscures the reality that sand must be extracted from neighboring territories, particularly Malaysia and Indonesia. Singapore’s sand extraction has perpetuated a clear and present eco-danger for its neighbors, while abetting its own territorial expansion.

Land acquisition by HDB

The Land Acquisition Act of 1966 empowered the state to take posession of any land for the purpose of national development. As a result, the majority of Singapore’s land was placed under state control, and HDB forcibly rehoused large populations from kampongs, shophouses and squatter settlements to high-rise HDB flats.

This imposed resettlement to state-controlled and surveilled ‘barracks’ was violently enforced, where those who resisted faced demolition teams and police riot squads. The housing project saw the majority of the population taking on mortgages that they’d have to pay back to the state, creating a dependency on waged work. At its core, this dispossession was really about removing alternatives to subsistence outside of waged productive labour that complies with capitalism.

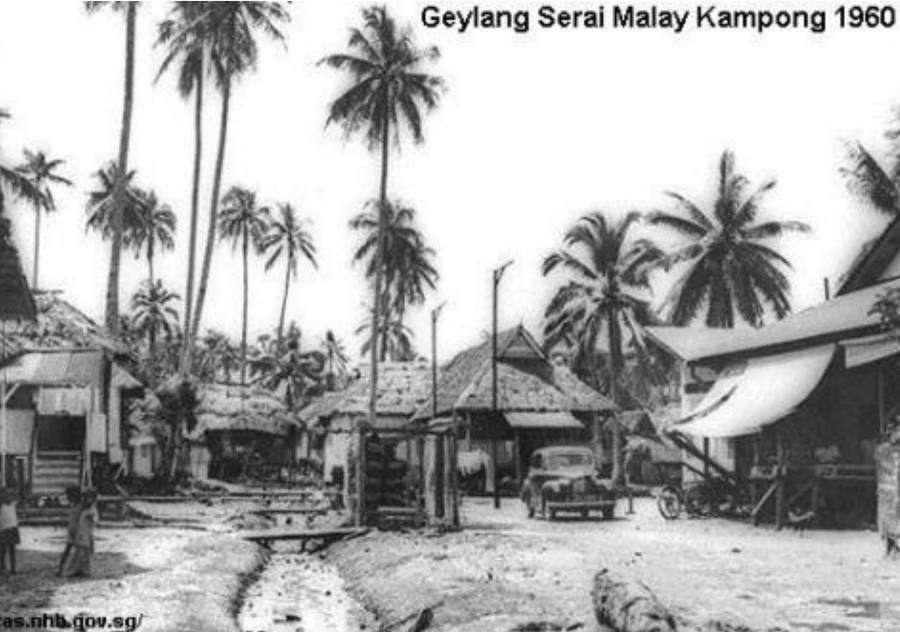

Kampongs and their sustainable relationships with the surrounding land and sea provided important means of subsistence. They were also important spaces for community, serving as sites of organic solidarity.

A key state narrative about the HDB project is that the state transformed the ‘slums’ and ‘unhygienic settlements’ into something ‘modern’ and ‘pristine’. However, the reordering and restructuring of the land by the state was violent and forceful, and became one of the bases upon which Singapore capitalism accumulated and consolidated wealth for the elite.

Exploitation of migrant workers in Singapore

Many ‘crime control’ strategies in Singapore are geared towards restricting and disempowering migrant lives. This appears in the enforcement of labour conditions through immigration regulations, such as tying workers to employers, severely limiting access to citizenship rights, and the constant threat of deportation.

Migrant workers are also displaced from daily Singaporean life and contained within migrant dormitories and areas, excluding them from meaningful social spaces. The state’s ‘security’ mechanisms—ranging from border control, surveillance, policing activities on the street, to deportation—underpin modes of generating profit that depend on the exploitation of migrant lives. While the state crafts narratives that migrant workers are a dangerous class, in reality they face much higher forms of harm and violence and are more likely to be victimised.

Commodification of Security

Arguably, the Singaporean state justifies itself on the basis of delivering and upholding ‘safety’. As a result, ‘security’ has become a central and expanding feature of the economy, and thus a central source of employment as we see in security guards, cybersecurity, firms delivering security technologies, etc. Intensive collaborations between private security (G4S, Serco, etc.) and the government demonstrate that these mechanisms extend across public and private spaces.

Regulating Political Dissent

The state strives to stabilise the perpetuation of these modes of ‘security’ in part through internal security projects (such as Operation Coldstore), the use of detention without trial, and regulation of civil society. The suppression of political dissent reinforces the participation and continuity of productive labour, thus protecting the accumulation of state and elite wealth.

Capitalism sells poison of ‘security’

Dispossession, exploitation and commodification are interconnected pacification processes to enforce productive labour. They are all tied to the use of violence and coercion to secure the viability of the economy and thus of the accumulation of wealth by the state and the elite.

“The defining characteristic of capitalism, therefore, is its ability to productively sell insecurity to those it makes insecure — in effect, to sell the poison of pacification as cure.”

References

- Steven Box (1983) Power, crime and mystification. Routledge.

- Rigakos, G. S. (2016) Security/Capital: A general theory of pacification. Edinburgh University Press.

- Chua, C. (2020) ‘‘Sunny island set in the sea’: Singapore’s land reclamation as colonial project’, in Cowen, D., Mitchell, A., Paradis, E. and Story, B. (eds.) Infrastructures of citizenship: Digital life in the global city. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, pp. 238-247.

- Tremewan, C. (1994) The political economy of social control in Singapore

- Greener, J. (2022). Moralising racial regimes: surveillance and control after Singapore’s ‘Little India riots’. Race & Class, 64(1), 46-62.

- Greener, J., & Naegler, L. (2022). Between containment and crackdown in Geylang, Singapore: Urban crime control as the statecrafting of migrant exclusion. Urban Studies, 59(12), 2565-2581

- Rigakos, G. S. (2016) Security/Capital: A general theory of pacification. Edinburgh University Press.